Over fifteen years ago, I opened a book that would change how I understood my own heritage.

I was a book reviewer for Multicultural Review, based in Florida. They regularly sent me books with Middle Eastern themes. One day, a package arrived containing My Father’s Paradise by Ariel Sabar.

I opened it. Started reading. And was stunned.

I was reading about Jewish families in Iraq who spoke Neo-Aramaic (dialects closely related to the one spoken by my own Chaldean community). Linguists estimate that Aramaic has been spoken continuously for over 3,000 years, making it one of the world’s oldest living languages.

It felt like discovering long-lost relatives through language.

That sense of recognition stayed with me. Years later, I had the honor of interviewing Ariel on a podcast about that very connection—the linguistic and cultural threads that bind our communities across centuries and continents.

The Babylonian Exile: A Shared History

When I became Executive Director of the Chaldean Cultural Center—home to the world’s first and only Chaldean Museum—I had the opportunity to explore an even deeper shared history.

The Babylonian Exile. 6th century CE.

[Image Placeholder: Chaldean Cultural Center Museum]

Through cuneiform tablets published in 2015, often referred to as the Al-Yahudu texts, we learned something remarkable.

Judeans in Babylonia were not enslaved, as many had assumed. According to research from archaeological studies, these tablets (dating from 572 to 477 BCE) document that Judean exiles lived with legal, economic, and civic rights remarkably similar to those of the local population.

They were part of the community. Neighbors. Woven into the fabric of Babylonian life.

As we planned the expansion of the museum, I knew we had to tell that story. Visually. Accurately. Responsibly.

I reached out to David Sofer, an Israeli-British collector whose Babylonian Exile materials are among the most significant in the world. He was extraordinarily generous—granting permission for images and replicas. Many of the original artifacts are now held in major institutions, including museums in Israel.

We wanted to honor this shared history. To show that our stories have always been intertwined.

Pomegranate: A Symbol of Blessing

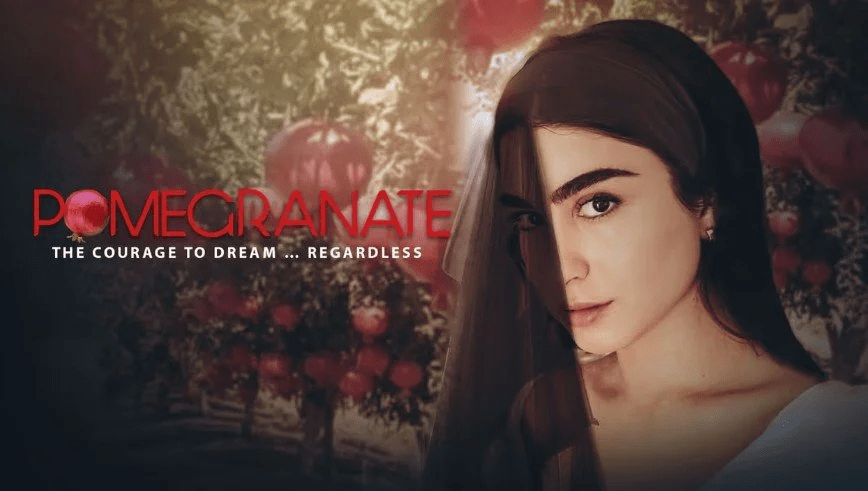

In 2016, I wrote a feature film titled Pomegranate.

Released internationally in March 2025, it’s traveled to over 25 countries and won 50+ international awards. But what makes it most meaningful to me is this: audiences everywhere—Jewish, Christian, Muslim, secular—saw themselves in it.

Iraqis love pomegranates. The fruit carries deep historical and biblical symbolism—fertility, abundance, blessing.

During my research, I learned something beautiful: rumman (pomegranate in Iraqi Arabic) comes from the Hebrew rimon (a symbol of blessing, abundance, and divine creation).

Even our words for this sacred fruit are connected.

That film became my most blessed project. In every sense of the word.

What We Share

On Wednesday, January 7, at the Detroit Athletic Club, history was made with the formation of the first annual Chaldean Jewish Alliance. What stood out most was how much we share—a message echoed from the podium by leaders including Sam Yono, Thomas Danish, and Rabbi Asher Lopatin.

We are both ancient peoples. Deeply rooted in faith and language. Both largely uprooted from our ancestral lands.

Today, only a few Jewish individuals remain in Iraq. In the 1950s, there were approximately 200,000 Jews living in Iraq. According to recent reports, fewer than five remain today.

The Chaldean presence continues to dwindle as well. The Chaldean population in Iraq has dropped from approximately 1.5 million before 2003 to fewer than 150,000 today (a loss of over 90% in just two decades). [Source: BBC News – Christians in Iraq]

We have both been displaced. Scattered. Forced to carry our heritage in our hearts instead of our homeland.

Yet what we have learned—again and again—is resilience.

Our histories teach us that survival is not only about remaining in a place. It’s about carrying memory, language, and faith forward.

When Chaldeans and Jews come together, we are not just remembering the past. We are affirming that our stories still matter. That dialogue itself is an act of hope.

Dialogue as Hope

Dialogue is an act of hope because it chooses curiosity over fear. Relationship over retreat. Shared humanity over inherited division.

We could focus on what separates us—different religions, different rituals, different paths.

But on the afternoon of January 7 we chose to focus on what connects us. Language. History. Displacement. Resilience. Faith.

The understanding that we have both carried something precious through centuries of turmoil. And that by sharing our stories with each other, we strengthen both.

A Final Thought

Fifteen years ago, I opened a book and felt recognition.

Today, I stood with a community and felt the same thing.

We are mirror reflections of each other’s history. We speak dialects of the same ancient tongue. We honor the same sacred symbols. We carry the same inherited memory of exile and resilience.

When Chaldeans and Jews come together, we remember that our survival is not just about us. It’s about every generation that refused to let the story end. Every family that passed down the language. Every person who said, “This matters. We matter.”

Thank you for being part of that act tonight.

Thank you for choosing hope.

And this is only the beginning of the work we will continue to do together.For more than 20 years, I’ve shared my work through books, workshops, retreats, seminars, and personal consultations. I love helping writers and creatives develop their voice, strengthen their craft, and bring their unique vision into the world. Learn more at weamnamou.com.