There’s a moment that happens when you step into a role you were meant for. Everything that felt difficult before suddenly makes sense. Everything you struggled to understand becomes clear. It’s not that the work is easy, it’s that it feels right.

That’s what happened when I became the Executive Director of the Chaldean Cultural Center and Museum.

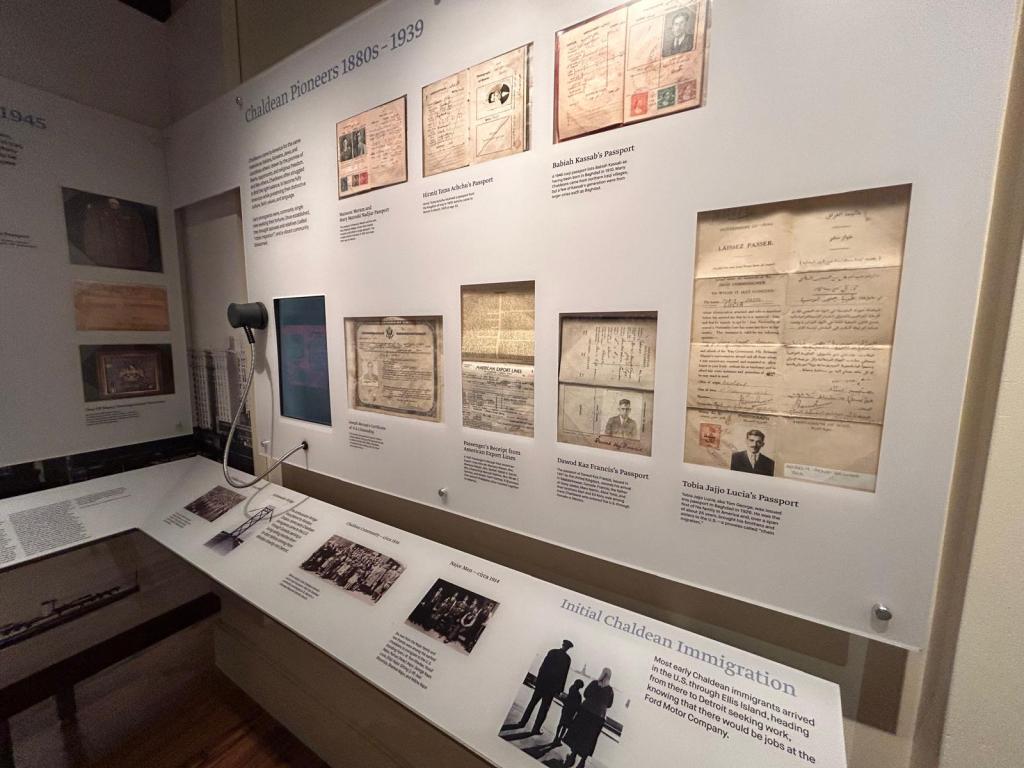

….she opened the entrance door to the museum. Before I reached the threshold, the sound of a mysterious foreign yet familiar music snuck through the doors like a streak of incense. Its pure and holy rhythm transported me to another world, one belonging to the ancients and the underground, where the spirits of my parents and ancestors greeted me, as if to say, “Welcome to our past.” I entered the ancient gallery of the museum, imbued with the colors of copal blue, olive green, and gold that subtly represented that region and its surrounding Tigris and Euphrates Rivers.

Judy explained that this was the Ancient Gallery, one of five of the museum’s galleries. It focuses on the five main empires that ruled in ancient Mesopotamia: the Sumerian; the Akkadian; the Babylonian; the Assyrian; and the Neo-Babylonian (Chaldean). The Ancient Gallery was a couple hundred feet, whereas the land it represented was about three hundred miles long and about fifteen hundred miles wide. We started with the Sumerians, and I was immediately transported to the stories of the people and places I’ve been reading about for over a decade, my people, my birthland, which I had heavily researched when writing my thirteenth and most recent book, Mesopotamian Goddesses: Unveiling Your Feminine Power. The book was published just four months prior to my visit to the museum and a month prior to my mother’s death. From that point forward, most of what Judy said and what I heard were two different things. I began to float along spontaneous streams of consciousness, my mind randomly taking me to where it wanted to go. Words I’d read over in the past suddenly appeared, organized into a partly historical, partly personal description of the Sumerians, who around 3500 BC, moved to the land between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in southern Mesopotamia, now called Iraq.

– Chaldean Museum is Chapter 12

Finding My Place

I’ve written before about my journey to this role, how I trained to be a docent at Cranbrook and struggled, how I served as Vice President of Detroit Working Writers and learned about community building. Each experience prepared me, but it wasn’t until I stepped into the Chaldean Museum that I understood what I’d been preparing for.

This wasn’t just a job. This was my calling.

As a Chaldean woman, I carry the stories of my ancestors in my bones. The ancient Mesopotamians, the Neo-Babylonians, the people who invented the wheel, developed agriculture, and gave us the first recorded writer in history, a princess and priestess named Enheduanna. This is my heritage. These are my people.

And suddenly, I wasn’t just learning someone else’s history. I was preserving my own.

What the Museum Taught Me

Leading the Chaldean Cultural Center and Museum taught me something profound about the relationship between community and personal growth. You can’t separate the two. We don’t grow in isolation. We grow when we’re part of something bigger than ourselves.

The museum became more than a building filled with artifacts. It became a gathering place. A touchstone for Chaldeans in the diaspora who needed to remember where they came from. A bridge between generations, where elders could pass down stories and young people could claim their heritage.

Every program we developed, every exhibit we created, every event we hosted was about community. About bringing people together. About saying, “You belong here. Your story matters. Your culture deserves to be preserved and celebrated.”

The Joy of Preservation

Being Executive Director meant carrying a beautiful responsibility. The Chaldean community has maintained its culture, language, and traditions for over 5,000 years. Our language, Aramaic, is one of the oldest living languages in the world. Our traditions connect us directly to ancient Mesopotamia.

The museum was about honoring that continuity. About celebrating the resilience and beauty of a culture that has thrived across millennia. About making sure that this rich heritage continues to be shared, celebrated, and passed down to future generations.

And I didn’t have to do it alone. That’s what community does. It distributes the joy. It shares the celebration. It says, “We’ll do this together.”

Community members donated artifacts from their families, each piece carrying stories of love and survival. Elders volunteered their time to share wisdom accumulated over lifetimes. Young people showed up eager to learn and connect with their roots. Scholars contributed research. Artists created works that honored our heritage. Everyone brought something to the table.

Leadership Through Service

My ancestors believed in a mindset of service. They saw their gifts and talents not as personal achievements but as tools to serve the greater good. Leading the museum taught me what that really means.

Leadership isn’t about being in charge. It’s about serving the community you lead. It’s about listening more than speaking. It’s about creating space for others to contribute their gifts. It’s about holding the vision steady while allowing others to help shape how that vision comes to life.

Every decision I made as Executive Director, I made with the community in mind. Not “What do I want?” but “What does the community need? What will serve our people best? What will ensure our culture thrives for the next generation?”

That’s what service looks like in practice.

How Community Made Me Grow

When I look back at my time leading the Chaldean Cultural Center, I see how much I grew. Not because I was working hard, though I was. Not because I was talented, though I brought my skills. But because the community lifted me up and helped me become more than I thought I could be.

Community members inspired me with their questions and insights. They offered perspectives that broadened my understanding. They encouraged me to reach for higher standards. They celebrated every victory with me and supported me through every challenge.

I learned to speak publicly with confidence because I was speaking about something that mattered deeply. I learned to advocate passionately because I was advocating for a community I loved. I learned to think strategically because the opportunity to make a difference was so meaningful.

But more than skills, community taught me about identity. About what it means to be Chaldean in America. About the sacred responsibility of carrying forward ancient wisdom in a modern world. About the healing that happens when we reconnect with our roots.

I grew because I was rooted in something larger than myself.

The Circle of Growth

Here’s what I’ve learned about community and growth. They feed each other in a circle that never ends.

Community helps you grow. You become more capable, more confident, more clear about your purpose. And then your growth serves the community. You bring back what you’ve learned. You lift others up. You create space for them to grow too.

And their growth feeds the community. And the community continues to flourish. And the circle goes on.

This is how cultures thrive. This is how movements build. This is how positive change happens. Not through isolated individuals working alone, but through communities of people committed to growing together.

Why This Matters Now

We live in a time when many people are searching for connection and meaning. There’s a growing hunger for authentic community, for spaces where we truly belong.

My time at the Chaldean Museum reminded me that community isn’t just nice to have. It’s essential. We need each other, not just for survival but for thriving, for becoming our fullest selves.

We need spaces where we belong. We need people who share our values. We need communities that call us to be our best selves and celebrate who we’re becoming.

Whether it’s a cultural center, a writers’ organization, a faith community, a neighborhood group, or a circle of friends, find your community. Show up for it. Contribute to it. Let it shape you. Let it inspire you. Let it hold you when you need support and celebrate with you when you reach milestones.

That’s where growth happens. In the fertile soil of community.

Gratitude for the Journey

I’m grateful for my time leading the Chaldean Cultural Center and Museum. Grateful for the community that trusted me with their stories. Grateful for the elders who shared their wisdom with such generosity. Grateful for the young people who showed up hungry to learn and eager to connect. Grateful for the board members, volunteers, donors, and supporters who believed in the mission and made everything possible.

That experience transformed me. It taught me who I am and what I’m capable of. It connected me to my ancestors and to my purpose. It showed me what’s possible when people come together in service of something sacred.

And it reminded me that we don’t grow alone. We grow in community. Always.